The Spirit Of Friendship

Some remarks on friendship I delivered at the annual meeting of the Friends of Suai/Covalima at the St Kilda Town Hall.

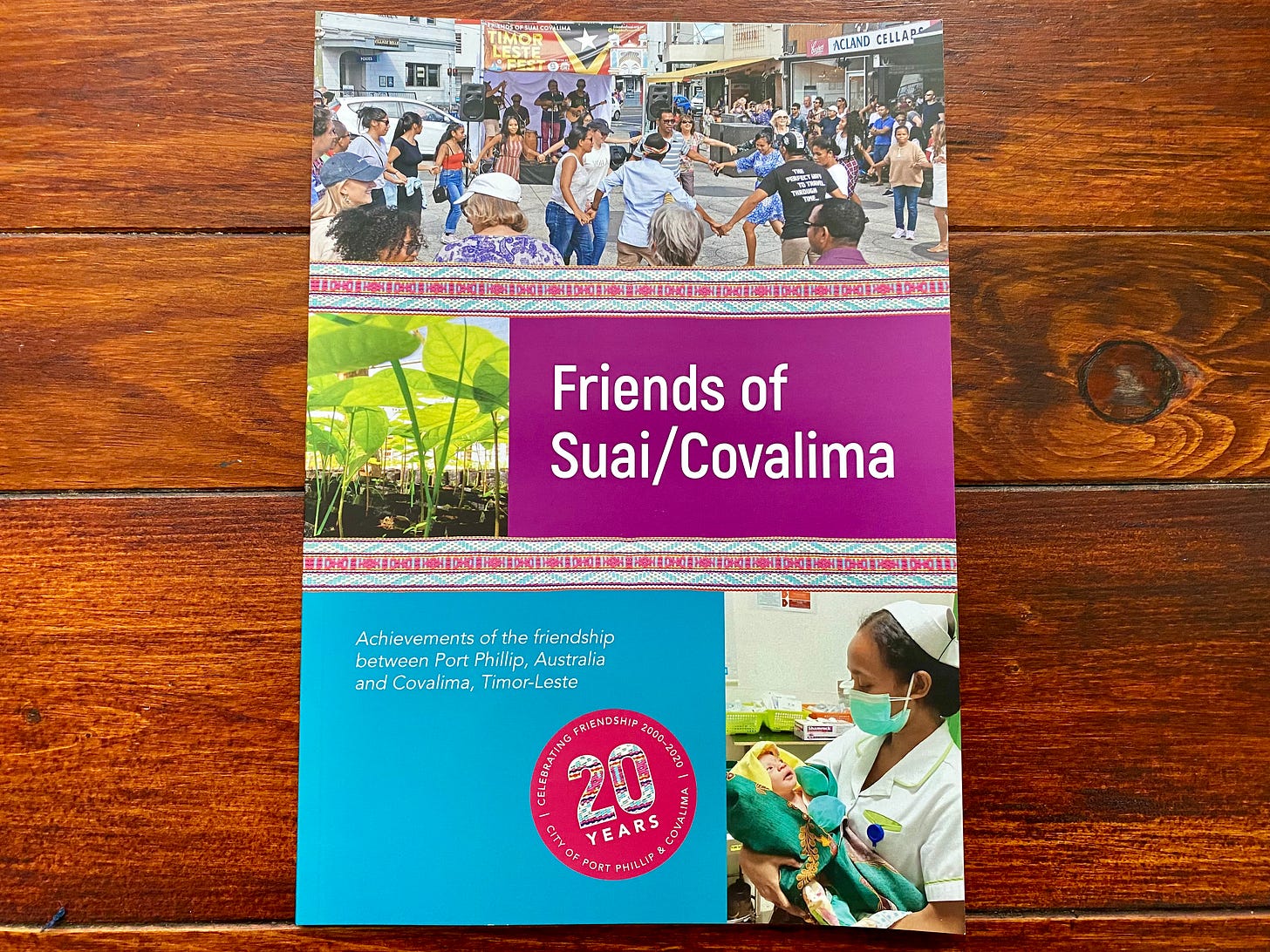

Last night I took the tram down to St Kilda for the annual community meeting of the Friends of Suai/Covalima. The friendship association has been running for over 20 years out of the City of Port Phillip local council in Melbourne. Port Phillip was the first council in Australia to sign a formal statement of friendship with Timor-Leste.

Within the friendship association local residents dedicate their time, expertise and enthusiasm to provide support and funding the Covalima Community Centre in the town of Suai in southwest Timor-Leste. It was a great honour to spend time with an incredibly lovely group of people who are highly committed to the development of the region and the country. And to the friendship between Australia and Timor-Leste.

I was there to present some insights from our recent paper at Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy, and Defence Dialogue (AP4D) titled: To Shape A Shared Future With Timor-Leste. However, prior to the discussion of the paper I gave a few brief remarks about the idea of friendship, and the important role that friendship associations play in building bonds of cooperation and trust between peoples and states. These remarks are below:

For the Ancient Greeks, friendship was considered an essential component of both a good life and a good society. Aristotle described friendship as being “a single soul dwelling in two bodies.” This is because friendship is reciprocal – it requires acknowledgement and commitment by both parties. This marks it as distinct from other relationships like parenthood which can exist outside of mutual acknowledgement – although ideally it would be best if it didn’t.

Aristotle saw the mechanics of friendship in three distinct models: utility-based, pleasure-based and character-based. Or, in other words, the usefulness of someone’s company, the joy that one receives from this company, or the recognition of character. This last model is considered the highest form of friendship – one that is built over time and based on deep bonds of confidence.

While each of these models could be understood as separate forms of friendship, it is also clear that they can work in conjunction with each other. Usefulness, enjoyability, and confidence can work in harmony to produce a compelling friendship. It is here, in this conjunction, where we are not only able to navigate the world as social animals but flourish within it. Both individually and together.

This leads to friendship’s importance to a good society – as it is critical to civic participation and to liberal democracy. The ability to exchange ideas freely and build common, mutually beneficial institutions necessitates that people act in good-faith with one another. And this good-faith requires a great deal of trust. While trust is often built off social norms and shared cultural attributes, these norms also need to be augmented with a more intimate understanding of each other. Our confidence in our systems needs to be reflected in the confidence we have in our fellow citizens on an individual level.

A friendship of confidence also requires a sense of duty towards one another. In recent decades the idea of duty has developed negative connotations – seen as a burden or something that imposes an outside authority on one’s self-interest. Yet duty is about the bonds of trust we have with each other. The communities we form, the social benefits and the securities we build. Duty also provides the personal rewards we gain from service.

To feel a sense of duty towards others is an opportunity to gain the most out of friendship. This may ostensibly be regarded as the utility of friendship, but it is also the goodness and pleasure of it. There is great joy to be had in assisting with the advancement of others. This is also how we gain a sense of purpose in life. For those who struggle with discontent, it is often a lack of duty and service that is at its root. It is within the duties of friendship where we often find our dignity.

An authentic friendship doesn’t need to be symmetrical. It can be based on each friend’s capabilities at a given time. While the investments we make in our friends should be reward enough themselves, if done so with grace and in a genuine manner they will also eventually be returned in various different forms. These returns may not be direct, but may instead exist in the realm of social norms that we all benefit from, and which we all have the agency to shape.

Which leads to an understanding of friendship in international relations. Australia is a developed country in a developing neighbourhood. We are also a country whose dominant culture is quite distinct from our neighbours. This gives us a unique set of responsibilities that most other developed countries do not have. It also means we need to make greater efforts to build bonds of trust. The relationships we build in our region are reliant on our character as a friend. Our ability to extend the hand of friendship in an authentic and committed manner. Confidence-building has to be central to our approach.

A commitment to common prosperity provides the bedrock of confidence neighbours have in each other. This should make Australia’s development assistance programmes a central pillar of its regional engagement. These investments should be seen as just the duty of friendship but also be understood as mutually beneficial. Not only because Australia gains the rewards from service and the joy of seeing its friends prosper but because a prosperous and flourishing neighbourhood creates an enormous stability and security dividend for Australia.

Friendship is often used as a term of description in diplomacy between states, and we should not view these pronouncements with cynicism. But often formal leader-to-leader level engagement can seem stiff and unnatural. Politicians are generally quite awkward with basic social skills. However, true bonds of friendship should have an ease of interaction. This comfort with others is, of course, built with time, investment and familiarity.

This is where friendship associations can prove an enormous diplomatic tool, as well as provide the building blocks of a good international society. As organisations that make the effort to invest their time and resources in a particular region or sub-group, they develop the intimacy necessary for genuine friendships to emerge – on an individual, regional and state level. They play a significant role in cultural diplomacy and relations, alongside the advancement of positive development outcomes.

Friendship associations serve all three strands of Aristotle’s model of friendship at the same time. They have a utility by assisting a region or group to develop, the pleasure of witnessing and serving these communities, as well as the rewards gained from understanding new cultures and ways of living. There are also the individual personal friendships that form from the work of friendship associations. Lastly, there is the character of consolidating these friendships into bonds of intimacy and trust.

Friendship associations strive towards an authentic form of friendship. They focus on bringing improvements to the day-to-day lives of the people they engage with. This approach is based on an understanding that other people’s lives are as real and vital as our own – that they are worthy of the opportunity to flourish. In this manner, friendship associations can become one of the most effective actors in public diplomacy – creating confidence and a denser network of social bonds that feed up into state-to-state level partnerships.