Week 21: Ice Ice Baby

A week in Reykjavik, and the important domestiques

I’ve been in Reykjavik this week. A homecoming of sorts, given my partner spent 16 years living here, and I spent 6 months here a couple of years ago. Having familiarity as well as a network and infrastructure of friends makes the experience of travel far more intimate. We weren’t here really to see things we’ve already seen, it was mostly just a chance for my partner’s daughter to reconnect with her friends. As we were staying with friends, the trip has been more about the daily domestiques* of life.

*I’m reappropriating this word away from its original French and its subsequent adoption by cycling, as I think it is the best descriptor I can find for the routines of everyday living – the kitchen table conversations, the ferrying of children around via the bus, cleaning, trips to the supermarket etc. As someone whose personal drive is bound to a sense of duty over the pursuit of pleasure, these domestiques are where I find worth.

Due to its climate, negotiating these daily tasks are often part the battle/charm of Iceland. Although it was the week before summer, the temperature has failed to reach 10 degrees, with the wind chill often in the minuses. But with the 6 months I spent here previously having been through the winter I feel I had built the resilience to negotiate the weather comfortably (and enjoy it in certain ways). The $600 jacket I bought in Sweden last November also helped.

Reykjavik has the familiarity of a European city, but the strangeness of also feeling like being on the edge of the world. Icelandic people are highly educated and cosmopolitan, but also have a strong attachment to their own unique traditions and culture. Especially the Icelandic language. Despite Icelanders having native level fluency of English, they make a concerted effort to resist the adoption of loan words into Icelandic for scientific or new and emerging concepts. Instead choosing to create new compounds from existing Icelandic words to express these ideas.

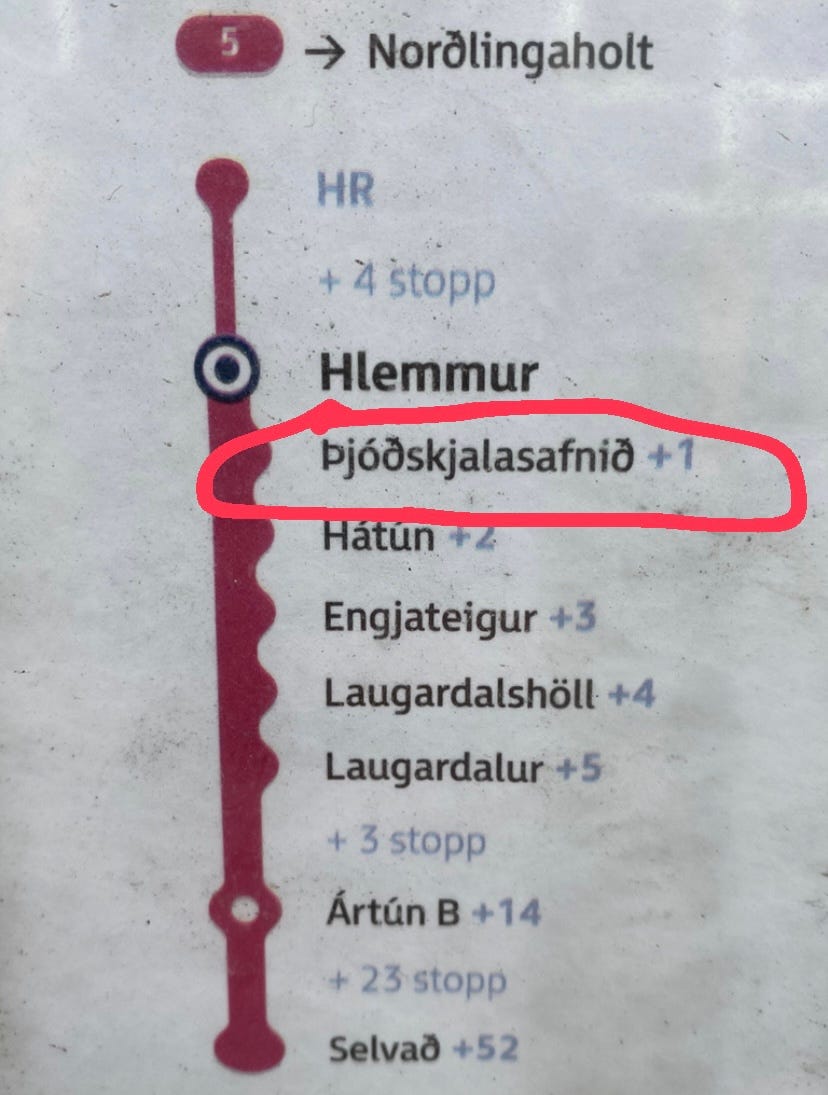

Given that Old English and Old Norse had a certain amount of mutual intelligibility, once you start to dig into Icelandic you can see the connections, particularly how English may have evolved had it not been flooded with French (what we speak today is effectively Franglais). Both English and Icelandic maintain two distinct “th” sounds, which Icelandic represents through þ and ð, but which English – unfortunately – replaced simply with “th.” (þ is the “th” sound of “things” or “through”, while ð is the sound of “that” or “the”).

The incredible look of Icelandic enables you to find some small enjoyments while waiting at bus stops.

While I was here I had hoped to meet with Iceland’s home-based ambassador to Australia. Although Iceland has no embassy in Australia, there are still connections and relations to be had, and I thought it would be good to find out where the issues of cooperation lay. Unfortunately, I was informed that the ambassador had just retired, and relations with Australia are now being conducted out of Iceland’s embassy in Denmark. As Australia’s embassy in Denmark has responsibility for Iceland, this makes sense.

As my professional focus is Asia-centric, I thought there might be a good opportunity to educate myself on how Iceland navigates the world, and in particular the politics of the Arctic Circle. Yet I didn’t get around to attempting to organise any other meetings, so I leave on Tuesday a bit empty-handed (or empty-headed). But we will be back here in September, so I will make a greater effort for it to be a trip of discovery of Iceland’s foreign policy, as I think it’s a fascinating place, and I hope that you will think so too.

This Week’s Reading:

Chinese Courts Want Abused Women to Shut Up

Natalia Antonova - Foreign Policy

“The fact that authoritarian societies are more brutal seems intuitive. Why shouldn’t a coercive state create coercive relationships between its citizens?

Yet the mechanisms of how authoritarianism breeds intimate partner violence in particular are rarely considered—even though authoritarian regimes tend also to be reactionary and patriarchal ones. For many years, domestic violence was seen even by dissidents and critics as a personal matter, far removed from the high and mighty machinations of the state. Writers, mostly male, who were eager to consider the impact of the gulag or the Cultural Revolution had no space for thinking about ordinary home life, especially about women.

For an abuser who lives under an authoritarian system, the freedom to destroy another human being—as long as she is female and lives under the same roof—can appear almost intoxicating, a chance for revenge against all perceived and real wrongs. He cannot express his rage at a controlling system that emasculates him, but he is allowed to have an outlet inside his marital home.

As long as the violence happens within the home, or the confines of a relationship, it is no threat to the family harmony model the Chinese government is pursuing. If anything, in this perverse understanding of harmony, violence enhances peace, by making sure the woman remains wholly subservient.

It’s not just family ideology that keeps the system on the side of the abuser. In this sense, violence against a woman is a convenient outlet presented to an angry man by an authoritarian state apparatus: “Sure, we will tell you what to do. But we will also provide you with the opportunity and the excuse to tell someone else what to do—with your fists if necessary.”

America’s ‘Neoliberal’ Consensus Might Finally Be Dead

David Wallace-Wells - New York Times

NB: I used to despise the word “neoliberal”, due to its overuse and the way it is used indiscriminately to mean “economically bad” rather than a specific set of ideas. And also used to describe political parties like the BJP, which is fundamentally false (they are a party with a deep suspicion of markets). But I’m starting to come around to the term as being useful when used accurately.

“The “new consensus” has meant enormous state investment, directed toward industrial revival all around the postindustrial world. But it’s not yet obvious that such a revival is truly workable — “Can the World Make an Electric-Car Battery Without China?” a headline in The Times recently wondered — which is one reason many regard that new economic world order as an expression of geopolitical rivalry more than industrial policy pursued for its own sake. Not long ago, China’s green-tech manufacturing boom looked like a possible climate lifeline; today it is more likely to be described by American bureaucrats as a suspicious display of rivalrous statecraft. And it is somewhat disorienting, even for critics of neoliberalism, to be heading into an escalating trade war without an ideological banner flying above. Hardly anyone at any point on the American political spectrum is talking about open markets and free trade in those once-familiar absolutes.

How profound is the change, beyond the rhetorical turn? In many ways, perhaps smaller than it may sound — the ships of state and business are large and hard to redirect, with small turns often hailed (or denounced) as total reversals. And the turn is motivated by some genuine and indeed progressive reckoning with the shortcomings of the old consensus, or at least its promises and presumptions, which Sullivan was careful to highlight in his speech: that markets were always efficient and productive, that all growth was good growth and that globally, more of it would mean more prosperity and inevitably a liberalisation of the world’s more autocratic and repressive regimes. On the domestic front, the implication is clear: a recognition that the free-market policies of the past several decades have punished the American working and middle classes, particularly in politically sensitive areas of the Rust Belt. Or, in the language of the campaign trail: Trade deals need to benefit the people of Pennsylvania and Michigan rather than those of Shenzhen and Shanghai.”

The Uncertain Result of Thailand’s Unambiguous Election

Tamara Loos – Foreign Affairs

“Move Forward’s success in the election is a measure of the groundswell of impatience with the prevailing order. But thanks to the intricacies of the electoral system devised by the military, the verdict of the polls cannot easily be translated into change. Few of the appointed senators will back a candidate from Move Forward or Pheu Thai. To form a government, Move Forward might have to compromise on its campaign pledges and stitch together a coalition with a military-backed party; if it does so, it will in effect be choosing power while forfeiting the chance to discuss and potentially reform Article 112.

This distressing pattern persists in Thai politics: when events or protests threaten the power of the military-monarchical status quo, the military uses the disruption as an excuse to stage a coup, crack down on dissent, and eventually hold elections for a new government, which rules until its power is threatened anew. What rationale allows the military’s continued stranglehold on democracy? The answer, in short, is the fear that democratic processes will lead to a decrease in the status and power of both the monarchy and the military, institutions that reinforce each other. King Vajiralongkorn, the various military-backed parties, and Prayut have an opportunity to accept the will of the majority of Thai citizens and open the door for reform. But this seems unlikely. Until Thais can hold a public conversation about how power operates behind the scenes in their country, it will be difficult for reform to take root.”

Pakistan’s Chaos Is Not Good News for India

Mohamed Zeeshan - The Diplomat

“Instability also brings sundry risks for New Delhi on the whole. Khan’s predicament has decimated the legitimacy and credibility of not only the fragile ruling coalition but also Pakistan’s powerful army itself. In a Gallup survey that came out only weeks ago, Khan was crowned Pakistan’s most popular leader with approval ratings of 61 percent — far ahead of the country’s current rulers. It’s well possible that Khan’s popularity has only been bolstered by his arrest, subsequent release, and the ruling establishment’s crackdown on his party. The fact that Pakistanis from across cities were willing to storm the streets and attack military installations — in a country where the army has held the keys to power for decades — is an ominous and unprecedented sign of Khan’s popularity. The stage is now set for a prolonged showdown.

For India, such instability often breeds volatility on the border. In the distraction caused by the chaos, militants targeting India may see a potential opportunity for a cross-border attack. In 2008, months after a chaotic movement ousted former President Pervez Musharraf, militants launched one of the deadliest terrorist attacks on Indian soil in Mumbai. In the ongoing crisis, the army’s ability to control such actors stands heavily compromised — thereby leaving India’s border security that much more precarious.

For its part, faced with an unprecedented crisis of credibility, Pakistan’s army may itself try to reassert authority by sparking hostilities with India along the border. For decades, Pakistan’s army has sought to reassert control at home by presenting India as an existential threat that only the military can counter. With tensions currently running high between New Delhi and Islamabad, that opportunity lies wide open.”

Modi In Papua New Guinea: Leader Of The Global South Or Quad Partner?

Joanne Wallis & Premesha Saha – The Strategist

Yet India’s credentials as a leader of the global south with a proud history of anti-colonialism seemed to be undermined by its exclusion of New Caledonia and French Polynesia—both of which have active independence movements—from the PNG summit on the grounds that it was ‘limited to independent and sovereign nations’. That hadn’t stopped the US from inviting them to its first US–Pacific Island Country Summit in September last year.

Modi’s pledges to Pacific leaders during the PNG summit will be welcomed, particularly on shared priorities such as climate change and sustainable development. But his visit highlighted differences between India and its Quad partners in the Pacific islands region that in many ways represent a microcosm of broader challenges to their cooperation. It has also revealed contradictions in India’s role as a leader of the global south. It’s not unusual for states to adopt contradictory foreign policies, but whether they can be sustained is another issue.

Ukraine in the New World Disorder: The Rest’s Rebellion Against the United States

Fiona Hill – Lennart Meri Lecture 2023

“Countries in the Global South’s resistance to U.S. and European appeals for solidarity on Ukraine are an open rebellion. This is a mutiny against what they see as the collective West dominating the international discourse and foisting its problems on everyone else, while brushing aside their priorities on climate change compensation, economic development, and debt relief. The Rest feel constantly marginalized in world affairs. Why in fact are they labeled (as I am reflecting here in this speech) the “Global South,” having previously been called the Third World or the Developing World? Why are they even the “Rest” of the world? They are the world, representing 6.5 billion people. Our terminology reeks of colonialism.

The Cold War era non-aligned movement has reemerged if it ever went away. At present, this is less a cohesive movement than a desire for distance, to be left out of the European mess around Ukraine. But it is also a very clear negative reaction to the American propensity for defining the global order and forcing countries to take sides. As one Indian interlocutor recently exclaimed about Ukraine: “this is your conflict! … We have other pressing matters, our own issues … We are in our own lands on our own sides … Where are you when things go wrong for us?”

Aris Roussinos - Unherd

“The post-1945 order, in the simplistic folk wisdom that only fully took shape with the fall of the Soviet Union, adopted the comforting myth that the Allied victory in the Second World War, like the Western victory in the Cold War, was a product of superior liberal-democratic forms. Shedding their overseas possessions in the decades following the war, Europeans flattered themselves that the age of empires was over, but that even as their physical power waned, their moral example would still guide the world.

Instead, the consolidation of the world into continental empires was only beginning. Political morality does not come into the picture: Europe’s conquest and post-war division into two rival spheres was simply the product of America and the Soviet Union’s vast industrial output, and the abundant raw materials, derived from ruthless territorial expansion and genocide in the preceding centuries, which enabled them to feed their factories.

Power flows through a million factory chimneys, and both Covid and the war in Ukraine have revealed to Europe’s feckless and misguided rulers how weak our continent has allowed itself to become. But both crises have also finally brought that fragile, complacent boomer, the world born in 1945, to a close: the entire worldview of its political avatar, Angela Merkel, now stands repudiated, even if no fully-formed replacement has yet arrived. First there were two rival empires, then one unchallenged hegemon, and now a series of potential challengers stand on history’s stage. Belatedly, European leaders are realising that unless it can defend itself, and provide for itself, then as Macron warned, “Europe will disappear.”

Will Lloyd – The New Statesman

“National Conservatism, defined by a deep revolutionary distrust of existing institutions, hostility towards the media, a communitarian ethos, an embrace of patriarchal morality and pessimism about America’s future, is reshaping the GOP from within. Hazony has successfully created a counter-elite in the Republican Party. The question that was brooded over in the Emmanuel Centre was whether the same might happen to the Conservatives in Britain.

These speakers bemoaned the loss of faith, of unity, of values, of babies. They resented the false promises of liberalism…The NatCons did not seek to explain the present. They vilified it. All they wanted was for people to be together again, for a new faith, new fixed standards, and freedom from all the rocketing doubt that comes with unlimited choice. That was the core of National Conservatism. A terrible loneliness and all the hopeless resentment that sprang from it.”

The Case For Pro-Democracy Rituals

Brian Klass - The Garden of Forking Paths

“The founding father of sociology, Émile Durkheim, coined the term “collective effervescence” to refer to the power of ritual. It’s a feeling of shared harmony, communal belonging, that inevitably emerges when people participate in a ritualistic act, a crowd that subsumes its members with an overwhelming sense of oneness.

The Trump rally is the most intricate and elaborate locus of collective effervescence in the MAGA movement, but it’s not alone. Consider the boat parades. (Yes, remember those?). Or CPAC. The entire political apparatus around Trump is action-oriented, ritualistic, and communal. Weird, yes, but astoundingly effective.

It’s authoritarian super glue.

The modern battle between authoritarianism and democracy is too often an unfair fight, with one group perfecting exciting methods of social cohesion, capitalising on our craving for collective effervescence, all while those who oppose them remain woefully atomised, rejecting ritual, the mechanism best suited to fight back.”

J.S. Mill vs The Post-Liberals

Richard V. Reeves - Persuasion

“Mill believed that the pursuit of truth required the collation and combination of ideas and propositions, even those that seem to be in opposition to each other. He urged us to allow others to speak—and then to listen to them—for three main reasons, most crisply articulated in Chapter 2 of On Liberty.

First, the other person’s idea, however controversial it seems today, might turn out to be right. (“The opinion … may possibly be true.”) Second, even if our opinion is largely correct, we hold it more rationally and securely as a result of being challenged. (“He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that.”) Third, and in Mill’s view most likely, opposing views may each contain a portion of the truth, which need to be combined. (“Conflicting doctrines … share the truth between them.”)

For Mill, as for us, this is not primarily a legal issue. His main concern was not government censorship. It was the stultifying consequences of social conformity, of a culture where deviation from a prescribed set of opinions is punished through peer pressure and the fear of ostracism. “Protection, therefore, against the tyranny of the magistrate is not enough,” he wrote. “There needs protection also against the tyranny of the prevailing opinion and feeling.”

Mill never pretended that this would be easy, either at a personal or political level. The humility and openness that is required is hard-won. Our identity as a person must be kept separable from the ideas we happen to endorse at a given time. Otherwise, when those ideas are criticised, we are likely to experience the criticism as an attack upon our self, rather than as an opportunity to think about something more deeply and to grow intellectually. That’s why education is so important. Liberals are not born; we have to be made.”