Week 32: Hungary Like The Wolf

The romantic great European cities, and the political dangers of this romance

Since my train trip from Tallinn to Riga, I’ve moved down through Krakow and on to Budapest, and now find myself cat-sitting in London for a couple of weeks. London is my spiritual home, the place I feel most comfortable in, and the city I am always desperate to get back to.

Aside from being in London, there only really two other things I like in this world –either being in bed on my laptop staring relentlessly at the internet, or being on the move. Destinations are fine, but actually getting from A to B is what I care about. I love to move, and to move with intent (one reason why I love good public transport).

Although I usually prefer to travel by train, the train from Krakow to Budapest goes via Bratislava and takes about 10 hours. I was looking to maximise my time in Budapest, and the bus takes a direct line and makes the journey in only six hours. So I took the bus. Which happened to be a very nice scenic route through the hills of Slovakia.

I’d never been to Budapest before and it immediately struck me as my kind of city. It’s dense and walkable, with an excellent metro system as well as a decent tram network. With Hungary’s hot summers, it also feels alive, spilling out on to streets with constant activity.

There’s also a certain romanticism to the Danube River, how it winds through Vienna, Bratislava, Budapest and Belgrade. With the river being the great connector of trade and culture in these urban centres before trains, cars and planes.

One can’t help but fall into romanticism when travelling through Europe. The gorgeous old cities with these grand histories are compelling for those of us who live in more modern ones.

However, we need to be wary of how this sentiment translates politically. Romance can often be blinding, and can be thoroughly dangerous at its worst. Yet we should also recognise the importance of protecting of history and culture. How we balance this things is a great political conundrum.

Protecting history and culture needs to find a way to be different from the political movements that seek to manipulate these romantic sentiments for the concentration and abuse of power. In Hungary, this power has been obtained by Fidesz Party of Viktor Orbán.

Orbán has found a neat trick – take the practical advantages of being within the European Union, but set his movement up in opposition to the ethos of the project. This has been a way to increase his global influence, not solely his power within Hungary.

Of course, not everyone in Hungary succumbs to this kind of political manipulation. But even at the 2022 election, with opposition parties consolidating into a single bloc to counter the mechanics of the country’s voting system, Fidesz were able to increase both their percentage of the vote and their seats.

Although Fidesz has also used an array of different patronage schemes to effectively buy votes, there is clearly something about Orbán and Fidesz that people find attractive.

There’s a progressive habit of dismissing people who vote for such parties as simply stupid and racist. Yet that is a lazy refusal to think clearly about ideas and take people seriously. It often has the counter-effect of entrenching their mindsets.

So we need to think about why many Hungarians feels a sense of nationalist sentiment coupled with a resentment towards the liberal democratic norms that the European project embodies? Do cultures that have a deeper and more substantive history than a country like modern Australia have the right to feel pride in this and seek to preserve what they have built?

The caveat here is, of course, that Hungarian culture is in no way threatened at all. This is merely a political tool used by Orbán and the Fidesz Party to pursue and maintain power. But this tool is based on a distinct history within Europe that provides Orbán with some fertile soil to work with.

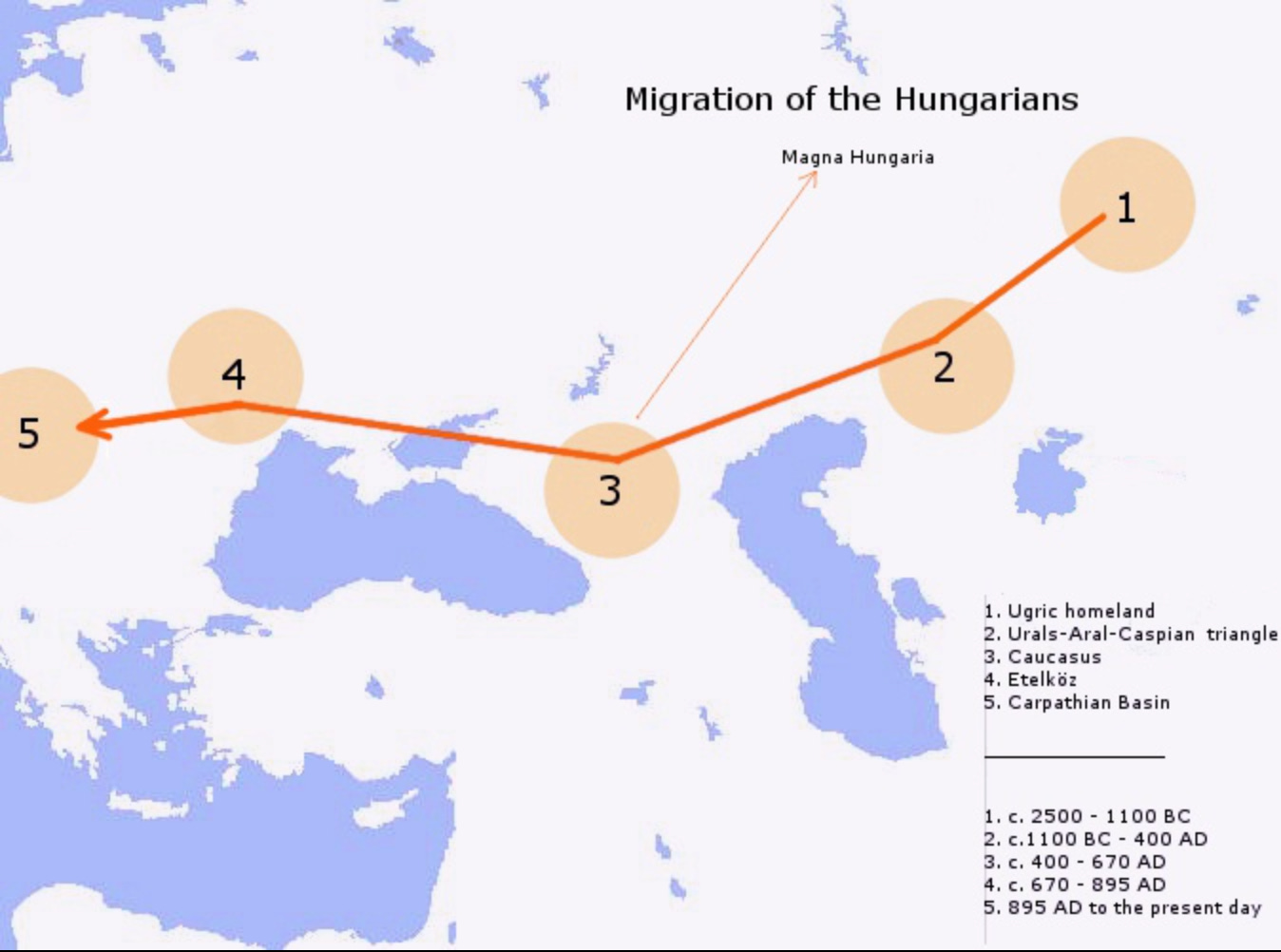

Hungarians are a unique people within Europe. Or, at least their language is. The Magyar tribes arrived in the Carpathian Basin around the 9th Century after an incredibly long period of migration from Western Siberia. Hungarian is a Uralic language, it is distantly related to Finnish and Estonia – both also originated in West Siberia – but after a few thousand years apart Hungarian barely resembles these two languages (given their proximately to each other Finnish and Estonia are close, but not mutually intelligible).

Despite this history, genetically Hungarians now only retain trace elements of their Siberian roots, having mostly been assimilated into the Slavic and Germanic peoples of Central Europe. However, what is interesting about this is that the language remained dominant even as its original ethnic roots diminished.

Language can impart different cognitive skills, but it also creates a cultural outlook. A language also contains a history. The Hungarians may no longer ethnically be a distinct people within Europe, but they still see themselves as such. It is the language that contains their history, rather than their DNA. Although whether linguistic nationalism is any better than ethnic nationalism is debatable.

So there is a historical narrative and sense of nationhood here that Orbán is able to use to his advantage. The Hungarian language can be deemed enormously successful to survive and thrive from its point of origin – with now around 17 million native speakers in and around Hungary, and in the diaspora. It has done so under conditions where it may have realistically been lost to more powerful languages. Yet the narrative of the language – and by extension Hungarians – of being unique and potentially besieged is a compelling one. Easily able to attached itself to the victimology of modern nationalism.

May I ask what makes you optimistic, Grant?