Week 46: Frustration vs Humility

Reading Eric Hoffer's book The True Believer, and finding solace and hope in Lesson In Chemistry.

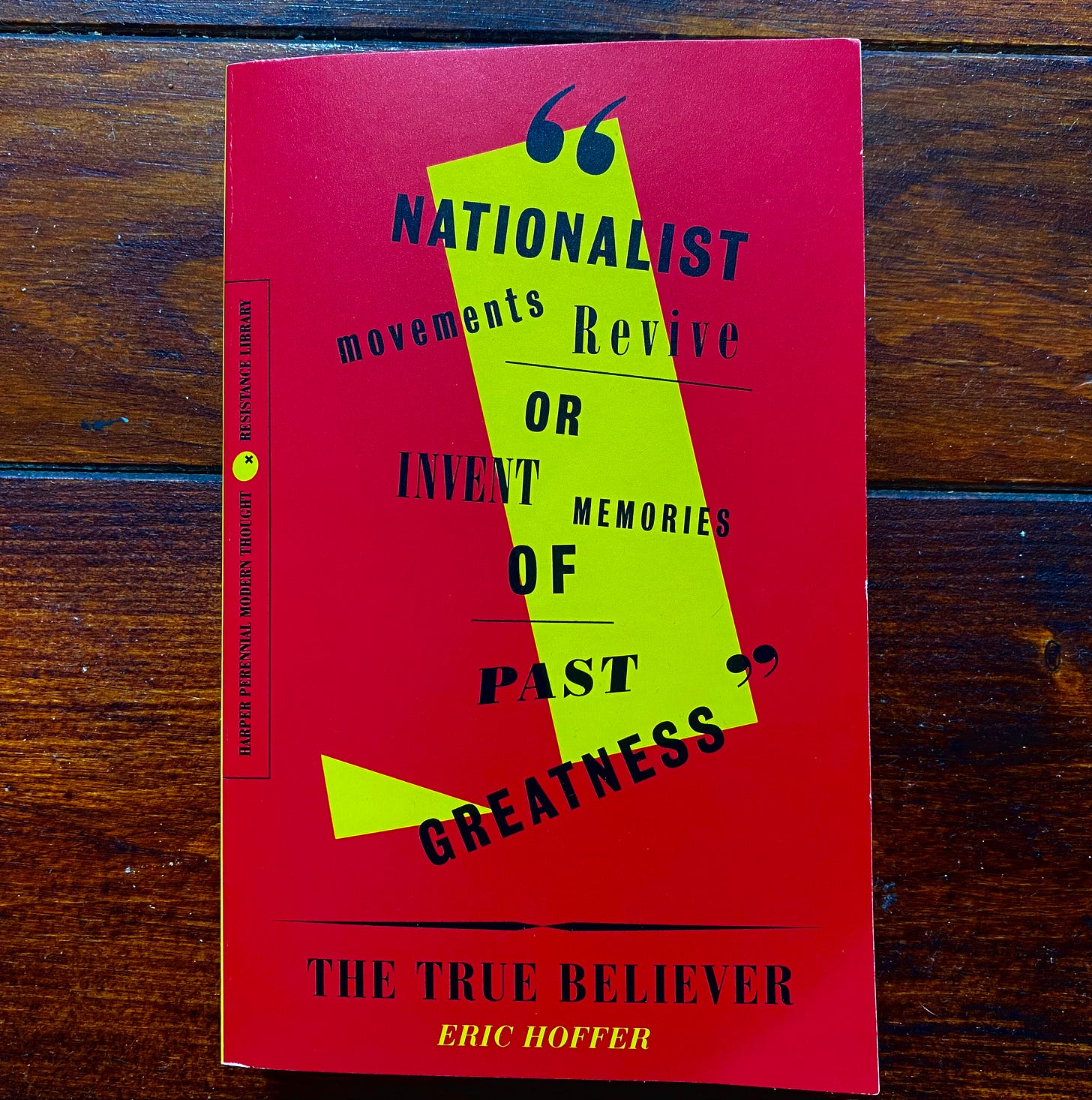

This week I’ve been reading a book called The True Believer by Eric Hoffer. The book is an examination of nationalist movements, fanatical causes, and the psychology of authoritarian figures and their followers. Although written in 1951, due to the permanent nature of these human dispositions, the book remains highly insightful into our modern-day fanatical movements.

To Hoffer the primary source of fanaticism is frustration. Yet, counterintuitively, this frustration often accelerates in conditions of improvement. It is not simply seeking to overcome suffering that creates mass movements, but it is born from the lusts we try to furnish and the belief that we are always owed more. It is this personal emotional insatiability that is harnessed by mass movements, regardless of the ideology. Movements that can cultivate the most frustration tend to find success.

Hoffer argues that the actual ideas of these movements are often irrelevant – what is most important is a hatred of the present. The movement that can offer a more realistic path to destroying the present is best able to gather these frustrated followers. In Weimar Germany the passions of frustrated young men were being cultivated by both Nazis and Communists. When the it became clear that the Nazis were in the ascendency, a great many Communists switched their allegiance. It was the allure of the destructive mass movement – and the desire to implement this destruction – that was the true motivating force.

What we should be paying close attention to these days are those movements that are purposely trying to cultivate and harness these frustrated and destructive impulses. We can clearly see the Republican Party has become one such entity. Particularly the way it needs to constantly enhance frustration and fervour through new aspects of the present to rage against. Guarding against these movements means being aware of one’s own frustration and those who seek to manipulate it. And most importantly having comfort within yourself as an individual, not as a member of a group.

Lessons In Humility

Over the past few weeks I’ve been watching a new mini-series called Lessons In Chemistry (adapted from the book of the same name). The show is set in the 1950s, and centres on brilliant chemist, turned cooking show host. It is excellent.

The most recent episode (released last Friday) struck me as something special. It was built around the correspondence between a chemist and a priest. These series of letters were ostensibly about the contest between science and faith, but were actually about the building of a friendship across worldviews and an open-hearted and minded approach to communication and interaction.

My attraction to this episode may be a case of being drawn into the rose-tinted nostalgia of a bygone era, yet I think that this is a form of hope as well as solace. At the moment I feel incredibly disheartened by the relentless cynicism of modern politics – and the social platform on which this is built. This bitterness, pessimism and distrust feeds upon itself, descending like a dense fog over our societies.

For an hour, at least, this episode offered a better path – one of being kind and gentle, genuine and curious. We can live these moments through fiction, or we can try and built them ourselves.

This Week’s Reading

Grant Wyeth – International Blue

“I would like to consider myself progressive in a broad sense – concerned with advancing the well-being of those less advantaged, and moving humanity towards greater cooperation and more widespread flourishing. Politics and policy should be kind and empathetic, it should be generous towards those in need, and built upon the idea that if good-faith is extended then it will also be returned. It should encourage a sense of community across all demographics.

But I don’t think this is what progressive politics is now about. It has become deeply cynical about human progress, believing it to be a chimera or a scam. Despite evidence that many previously marginalised groups have greater general respect and access to opportunity that they did decades ago, this steady forward movement clearly isn’t satisfying enough, instead this politics wants something more, something visceral and vengeful.”

Australia and Tuvalu: The Complexities Of Climate Refuge

Grant Wyeth – The Diplomat

“The history of the world is one of the rise and fall of nations. Cultures evolve, but they also disappear. Yet it is only in recent decades that have we come to fully understand what we lose when cultures disappear. When, for example, a language dies, a unique facet of humanity and ways of understanding the world die with it.

Despite this recognition, smaller nations continue to live precariously. Although we now have strong global commitments to cultural preservation, these efforts often struggle to resist the unstoppable force of larger, more powerful nations. Larger powers, due to cultural hegemonies or expansionist designs – either intentionally or unintentionally – tend to trample across the worlds of smaller nations.

Yet alongside the reality of the often unfair competition between cultural forces, we now have the unfair environmental force of climate change. Climate change is a force that smaller nations are not responsible for, but disproportionately feel the consequences of. Those nations whose geographies offer them little protection from these consequences face an existential crisis that is every bit as serious as traditional security concerns.”

The Middle East Has Locked Itself In A Slaughterhouse

Hisham Melhem – Foreign Policy

“Listening to Israeli officials speaking in English and Hamas leaders in Arabic, one could easily use their words interchangeably. With absolutist certainties and blind convictions, and driven by unbridled intensity, they have hurtled their world and those who live in it—and those on its periphery—into uncharted chaos. The warriors for a redeemed Israel and a liberated Palestine have declared, with words and deeds, the death of innocence on the other side. No one is to be spared. Not even a child, much less any abstract ethical idea, has sanctity when the long knives are clanging.

Both sides rushed to resurrect their conflicting narratives and revived the clash of their memories. Empathy with those civilians suffering beyond the veil of self-righteousness is forbidden, even treasonous. And if you are an Israeli, don’t you dare contextualise the conflict, lest you help your enemies.

Incitement, demonisation, and intimidation have followed in the wake of Oct. 7, along with groupthink, collective denials, and the extreme intolerance of even a hint of dissent, not to mention the trivialisation of the histories and experiences of both peoples.”

Why Are Jews Blamed For Israel’s Actions?

Jo Glanville – Prospect

“These ancient and familiar conspiracy theories are triggered when Israel sheds Palestinian blood. It becomes more than a state committing a war crime when it bombs civilians, but guilty of an atavistic evil that is seen as inherent in the Jewish people. And that guilt is perceived to extend beyond Israel’s boundaries. This is what Jews do and have always done. They collectively have blood on their hands—a calumny that dates back to the crucifixion and the claim that Jews killed Jesus.

As the Jewish state, Israel carries the baggage of that history. It has become the modern manifestation of this trope, rather than another country among many that are guilty of human rights abuse. We need to disengage the fictitious crimes of the Jewish people, which were the bedrock of antisemitism, from the actions of Israel. That means throwing off hundreds of years of indoctrination that begins with the Bible and runs through western political thought and the canon of western literature.”

Isaac Chotiner – The New Yorker

Interview with Omer Bartov

“What distinguishes genocide from crimes against humanity or ethnic cleansing?

There are clear differences in international law. War crimes were defined in 1949 in the Geneva Conventions and other protocols. They are serious violations of the laws and customs of war and international armed conflict, and they can be committed against either combatants or civilians. One aspect of this is the use of disproportionate force—that the extent of the harm done to civilians should be proportionate to your military goals. It could also be other things, such as the maltreatment of prisoners of war.

Crimes against humanity do not have a U.N. resolution, but they were defined by the Rome Statute, which is now the basis for the International Criminal Court. That talks about extermination or other crimes against civilian populations, and it does not have to happen in war, whereas war crimes obviously have to happen in the context of war.

Genocide is a bit of a strange animal because the Genocide Convention of 1948, on which it’s based, defines genocide as the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such.” And this “as such” matters because what it means is that genocide is really the attempt to destroy the group and not the individuals in that group. It can be accomplished by killing members of the group. It can also be accomplished by other means such as starving them or taking away their children, or something that will bring about the extinction of the group rather than killing its individuals.”

Emma Beals & Peter Salisbury – Foreign Affairs

“The world is at an inflection point, and it is still possible to galvanize support for a new approach to resolving conflict. To achieve this, creative and courageous leadership is needed from a broad coalition of politicians, business leaders, the UN, peace builders, and local communities—aligned with a renewed ambition to make peace. Without aspiring to, and placing a value on, sustainable peace, it is all too easy to accept least bad outcomes and to forget the enormous human and resource toll of doing so.

First and foremost, any effort at renewing peacemaking for the twenty-first century needs political will from powerful states, principally the United States and the other permanent members of the UN Security Council. This point was explicitly made by UN Secretary-General António Guterres in his recently published policy brief, “A New Agenda for Peace,” a vision that places the responsibility for securing the peace and upholding international norms in the hands of individual countries rather than the multilateral system. If governments that say they believe in a rules-based order—including those in Brussels, London, and Washington—are willing to uphold international laws and norms, then there may be some hope for the future. But if they are not, then the current race to the bottom is certain to continue.”

Why Activism Leads To So Much Bad Writing

George Packer – The Atlantic

“Once you join this game, it leads you straight into a tangle of hypocrisy and double standards. Earlier this month the government of Pakistan began to expel 1.7 million Afghans who had been living in the country for as long as 40 years. Border crossings filled with tens of thousands of poor and desperate people, stripped of money and possessions, without food, water, medicine, shelter, or any prospect of survival in Afghanistan as it nears its third winter under Taliban rule. #saveafghanrefugees did not take over social media. Universities and corporations didn’t issue carefully worded statements of concern that drew furious replies. American colleges didn’t erupt in protest. Young people in London and Washington didn’t wear burqas to show solidarity with Afghan women forced into lives of oppression and misery. Pictures of Afghan refugees weren’t put up on walls and torn down from walls.

When it comes to other people’s tragedies, we’re all hypocrites. No one can care equally about Israel/Palestine, Afghanistan, Syria, Darfur, Xinjiang, Ethiopia, Ukraine, Armenia, Mexico, and Lewiston, Maine. Personally and geopolitically, this inequity of concern makes sense; morally, it’s empty. Choosing sides means accepting these double standards, and you can’t choose a side without wading into a riptide of accusations, counteraccusations, and sheer dishonesty. Writers and artists swim in these waters at their peril.”

Maria Snegovaya, Michael Kimmage & Jade McGlynn – Foreign Affairs

“The core elements of Putin’s ideology are internally consistent, even if they are not codified in any one text. The first tenet is the imperative of a strong, stable Russian state. Echoing themes from both the tsarist and Soviet eras, this principle holds that the Russian state embodies the historical essence of the nation, which for centuries has persevered in multiple forms: the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and Putin’s Russia. It is the state, the narrative goes, that guarantees Russia’s great-power status and that guards the country’s traditional values and ways of life. Without the state, there is no Russia.

Statism connects to another component of Putin’s ideology: the safeguarding of Russian exceptionalism and the cultural conservatism that preserves it. This element promotes a near-messianic vision of Russia as a state-civilisation, borrowing heavily from fascist theories that have circulated for over a century and emphasising a civilisational and even racial aspect of Russian identity. Russia is not just a modern political entity—it is a civilisation, a historic people who possess a unique culture rooted in a traditional set of values and a love of the state. This framework is made plain in Russia’s newly adopted Foreign Policy Concept, which refers to Russia explicitly as “a distinctive state-civilisation” with a “historically unique mission” to ensure the development of humanity. This narrative gives ideological ballast to Russia’s efforts to challenge the existing global order and to its invasion of Ukraine as the defence of an imperilled Russian civilisation.”

How Discredited ‘Parental Alienation Syndrome’ Is Used To Cover Up Abuse

Carrie Leonetti – Newsroom (NZ)

“It is, as far as I’m aware, the only psychological disorder in the world that strikes primarily wealthy men – those who can afford to sustain years of litigation in the Family Court.

Instead of being heard and believed, children are subjected to a form of litigation abuse, being dragged into the offices of lawyers and psychologists, where they are worn down until they tell these professionals what they want to hear: maybe the violence was not that bad, maybe they were just telling Mum what she wanted to believe, and maybe they would be better off at Dad’s house.”

If there is one period and place where we could consider music to be at its peak, it would have to be 1980s Japan. The country was obviously experiencing a period of extraordinary economic boom which afforded its citizens the ability to become wildly creative. As a result, the inherent weirdness of Japan fused with Western pop and experimental music to produce some truly stunning records. This being a standout.