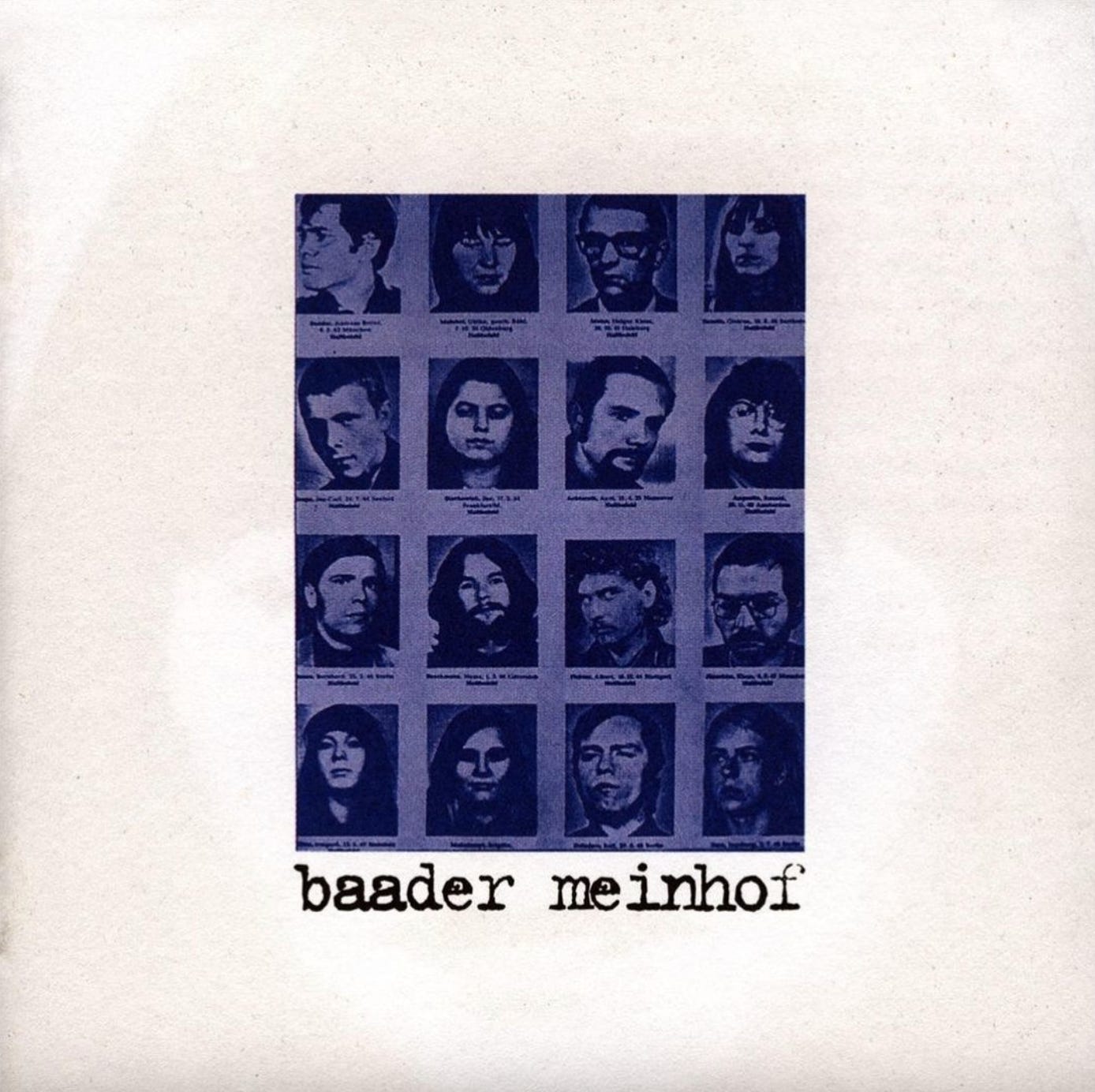

Baader Meinhof – Baader Meinhof (1996)

The Auteurs and Black Box Recorder's Luke Haines's emblematic concept album about the Red Army Faction

“The English have a justified reputation for being sturdy and prosaic, yet they have excelled at poetry above all the arts. They are often thought to be shy and retiring and even (by Hollywood especially) affected to the point of effeminacy. Yet few people have shown a more frightening and ruthless aptitude for violence. Their fondness for flowers and animals is a national as well as an international joke, yet there is scant evidence of equivalent tenderness in, say, the national cuisine. The general temper is distinctly egalitarian and democratic, even populist, yet the cult of aristocracy and hierarchy is astonishingly tenacious.”

63 Ways to Begin an Essay on Luke Haines – Paul Morley

The grand driver of humanity, according to the philosopher Georg Hegel, is our seeking of recognition. This desire for recognition may come in many forms, from the self-determination of nations, to the rights and dignity of individuals within societies, to striving for privileges above – and dominance over – others, or through personal success – in one’s career, through sport or art, and, of course, to the pursuit of love and companionship.

Recognition motivates both the grand triumphs of human ingenuity and humanity’s destructive impulses. It can be harnessed for the politics of practical improvement, or drag us down into the dark emotions of ideology. It is our permanent struggle, and each one of us undulates daily through the peaks and troughs of its validation and resentment.

At its best, this need for recognition inspires our creative impulses. What this psychological burden has unlocked has been astonishing in its imagination and vision. We are an animal defined by our innovations. And the great works of humanity far exceed our biological imperatives as merely one species amongst many on this planet.

Arguably there is no finer creative pursuit than music. Regardless of the style, music has the ability to be a universal language. It can resonate across cultures and generations, and often conveys far more than speech or writing. Its historical emergence within geographically isolated groups indicates that music is a higher form of expression housed deep within the human soul.

This connection with the soul has led to popular music to become the world’s dominant art form. However, due to our striving for recognition, it also spawned new groups, and competition between groups – from Teddy Boys and Mods, to Punks, Goths and Ravers – or at least it did in the 20th Century, before the internet flattened youth culture. For many, the style of music they listened to, or the bands they liked, was as powerful as any national sentiment. It fashioned habits and social behaviours as effectively as any broader customs or tradition. These musical subcultures found their spiritual home in the United Kingdom, where the weekly music press was able to cultivate a powerful sense of solidarity and antagonism.

This is what made the British music scene so compelling during the latter half of the 20th Century. There were, of course, good bands and good songs, but these were housed inside a culture that strove for something else. To be in a band in the UK was not simply to write, record and perform, it was a statement of intent, and a statement of conflict. It was something beyond just the healthy competition between artists – in the UK pop music was war. Bands were gangs, other bands were the enemy, and shots were fired via the music press.

Are four young men gonna change the world again?

Johnny & the Hurricanes – The Auteurs

To have a mouth on you was just as important as having a knack for a musical hook. Those who excelled at this game not only talked constant shit about their fellow musicians, but did so housing a broader social critique. Blur were middle class art school boys cosplaying as working class yobs and needed to be exposed as such, while Coldplay were insufferable bedwetters writing mawkish pap. The better mouths could take this verbal combat and redirect it towards British society-at-large. Unlike their American counterparts, political bands in the UK have always been very funny.

This is because the UK itself is very funny. The paradox of Britain is that it gives the sense that it is striving to improve fairness while simultaneously believing that life should not be fair. This is the arbitrary clip around the ears that drove many of Morrissey’s lyrics – that there are forces of power that one has to navigate, but the manner by which these forces slap you down is what gives you a good story.

The UK’s own permanent struggle is the symbiotic tension between the persistence of class and hierarchy and the relentless hostility towards it. It is both the motion and stagnation of the country, and what produces some of their best art. What makes this funnier is that the British aristocracy seem to believe that the masses are perfectly justified in being resentful towards them. This, of course, will get the masses nowhere, but tally ho they’re doing a fine job trying.

Resentment en masse is, of course, the UK’s national ethos – from the Scots and Welsh feeling ashamed of being conjoined to the English; to the more direct action against this reality taken in Northern Ireland; to the English’s own self-loathing and obsession with decline. It’s grim up north, and the south are effete wankers. The whole place reeks of discord and decay and that’s the way they like it. It is the compost in which their creativity thrives.

From Dungeness to the Isle of Wight

Would the last one to leave turn out the light

Goodnight Kiss - Black Box Recorder

Luke Haines strode into this environment in the early-1990s ready-made to kick against the pricks. He had a novelist’s eye for social detail, a dark dry wit, and a galaxy-size animosity towards whomever crossed his line of sight. He also had a certain fascination with violent subversion.

From the chauffeur fantasising about killing his boss on “Valet Parking”; his attempt to undermine the British tradition of the Christmas single with “Unsolved Child Murder”; having Sarah Nixey’s plummy vowels sing “Kidnapping an Heiress” on their Black Box Recorder project (an apt Haines band name); and seeking to out-shock the provocative conceptual artist Sarah Lucas by writing a song claiming to have killed her.

All this was pop to Haines, and all this was pop in the British tradition. The point was to be transgressive, but to house it in a catchy tune. There’s no point trying to offend people if it’s not going to be on Radio 1. And this is, after all, what the British want. To be the sick man of Europe, and to listen to his songs. The artistic pay-off from Brexit must be just around the corner.1

A debut album with his band The Auteurs nominated for the Mercury Music Prize provided Haines with the kind of recognition he would both disdain and crave. He was brought into the line of sight of those who hand-out official certificates of acclaim – and while such an authority Haines would regard as lacking legitimacy, he nevertheless believed he deserved their adulation. However, his wry, literate, well-crafted songs couldn’t compete with Suede’s sumptuous swagger, and the bitterness this left fuelled much of his subsequent work (despite Suede being the one band Haines claimed to actually like).

For this resentment to find its creative peak, Haines needed a concept to house it in. If the music industry itself was now his enemy, then the only way to force it to give him the recognition he felt he deserved was via extraordinary means. Lacking the genuine audacity to walk into the British Phonographic Industry office strapped with explosives, he did the next best thing – he wrote an album about the Red Army Faction, otherwise known as the Baader-Meinhof Gang.

Beginning in the 1970s and continuing into the 1990s, the West German terrorist group was responsible for a series of assassinations and kidnappings, bombings and arson attacks of government buildings, businesses and military facilities, as well as a plane hijacking in coordination with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Much of this activity was funded by bank robberies.

The RAF believed that the West Germany state was merely a continuation of German fascism, and in responding to the RAF’s violent actions the state would reveal its inherent oppressive nature. This would subsequently inspire an awakening of a revolutionary consciousness within the working class.

Putting aside the idea that the state responding to organised violence2 is somehow oppressive, what motivated the group was the fantasy of ideology. A belief in a predetermined series of events that can be jolted into a reality through certain stimuli. This is how a love of violence justifies itself, and how violence in pursuit of romantic and glorious causes is never deemed to be amoral by its perpetrators.

This kind of dogma thrives within the socialisation of groups. It preys upon people’s insecurities, giving them a sense of belonging, and a reason to conform. This conformity then compounds and intensifies within groups into fervour and zealotry. This is a desire for recognition at work – a belief that these ideas and activities will elevate a person in standing or infamy. Or deliver them raw political power.

Yet in their collective struggle for recognition, groups like the RAF frequently display an almost comical lack of self-awareness. Mired in projection, they fail to see themselves in what they claim to oppose. The legacy of the Third Reich actually existed within their worldview – a belief that fear is the most powerful motivating force, and it should therefore be the central organising principle of society. Whatever ideals they may have claimed to hold were simply a smokescreen in aid of this objective.

This is the hate socialist collective. All mental health corrected

Back On The Farm – Baader Meinhof

All this was great material for Haines’s style of songwriting. The Auteurs's songs like Idiot Brother and Modern History were built on a certain kind of social stupidity – people who operate with absolute surety but with limited self-discipline or contemplation. Such types have always been fair game for a biting British satire. In the RAF, Haines had found a subject matter where these traits were writ large. Where the intensity of belief and lack of restraint was in extremis.

The subject matter also allowed Haines to distil his own musical persona into the album in a manner more acute than his work with The Auteurs or Black Box Recorder. Ramping up the violence and building a more exaggerated social environment – with its own distinct hierarchies of power to navigate and absurd scenarios borne from the attempt. It also allowed him to highlight the unhinged posturing of the RAF. For Haines, unhinged posturing may be a positive, but, whether his own nihilism was real or affected, it was a sentiment certainly lay at the heart of the RAF.

“Some of the dumb ones just don’t understand. There’s no manifesto, there’s no formal plan. Just burn warehouse burn.”

Theme From ‘Burn Warehouse Burn’ – Baader Meinhof

While the preceding albums by The Auteurs were light on experimentation3, with the Baader Meinhof album Haines expanded his musical palette to meet the concept of the work. A deep funk bass synth evoked the 1970s peak period of the RAF’s activity, while tabla and Middle Eastern strings were designed to highlight the collaboration between the RAF and the PFLP. Haines’s raspy voice oscillates between detached deadpan and faux-drama, giving songs like Meet Me At The Airport and There’s Gonna Be An Accident their requisite satirical edge. It was an unique sound that elevated the album from an intriguing side project to being Haines’s meisterwerk.

What Haines had found in the RAF was a subject that not only highlighted his own gritty preoccupations, but one that resonated with the glamour of popular culture. To many who see radicalism in art and politics as being indistinguishable, the RAF were deemed cool. Victims are, of course, subjective to radical politics, and causes are easily rationalised. With a membership drawn from the educated middle classes, the RAF saw themselves as part of the creative intelligentsia, and were therefore able to garner sympathy within this cohort across the West. The RAF’s image has proved enduringly fertile for both film-makers and, more telling than ironic, merchandisers.

Rudi said we’ve gotta get wise and we’ve gotta get armed. It’s a security state operation. Rich kid with a gun.

Baader Meinhof – Baader Meinhof

What guided this sympathy was an instinct within the creative classes that passionate intensity should be at the forefront of human endeavour. The exhibition of spirit. The excitement of action. The thrill of violence. The belief there is a genuine form of human animation, pure in motive, and utopian in vision. This may have been deluded in its attachment to the RAF – or any political group, for that matter – but it remains a powerful craving.

While the creative classes may often be seduced by passion and ideology, Hegel’s intellectual forefather, Immanuel Kant saw the arts and sciences as a way of channelling humanity’s competitive instincts into productive outlets. Following World War II, the Brits put this theory into practice. As its empire declined, the UK developed a knack for directing these impulses away from conquest and domination into becoming a cultural superpower. With the arguable exception of Sweden, its per capita impact on popular music is unsurpassed.

From the 1960s onwards, the UK has produced an astonishing series of both ear-catching and eye-catching musicians. It housed a culture that incentivised both musical innovation and idiosyncratic personas. Yet this culture relied on certain social conditions to flourish – a persistent social hierarchy, the conformity of national manners and a communal form of emotional repression. Without these there would be nothing to kick against. Great art requires a personal revolution against received etiquette.

Certainly Haines saw his own music as a cultural insurgency. This was, after all, a man who titled The Auteurs’s live album No Dialogue With Cunts. Yet what Haines embodied was the UK’s peculiar form of national sentiment. To be British is to be engaged in one’s own personal struggle against Britain. What provides Britain’s habits, and its innovations, is the daily thrust and parry of negotiating its various contradictions and humiliations. To soundtrack this national terrain is both rebellion from it, and submission to it.

I will write the national anthem for England, Scotland and Wales.

I will seal my reputation in England, Scotland and Wales.

Winston Churchill said there's a war on in England, Scotland and Wales.

I'm at war with every last one of them in England, Scotland and Wales

England, Scotland, and Wales – Luke Haines

Yet his extreme embodiment of this national sentiment was also something that limited Haines as a popular musician. While other quintessentially British artists from David Bowie to The Smiths to even Belle & Sebastian were able to find traction outside of the UK with music that was very rooted in place, Haines’s pitch black humour and an antagonistic posture was never going to translate well across the Atlantic. There are few albums as bleak and sinister as Black Box Recorder’s debut – aptly titled England Made Me. An album so fundamentally alien to America’s culture of sunny optimism and earnest patriotism. Or the culture America had until its own crisis of recognition plunged it into an emotional spiral and authoritarian strife.

Luke Haines’s Englishness is so desolate and inhospitable that even the English are scandalised by it.

63 Ways to Begin an Essay on Luke Haines – Paul Morley

Hegel’s philosophy of history recognised that human beings’ self-worth is intrinsically tied to the value placed on them by others. An artist requires an audience, and although admiration and praise from critics and chin-strokers can elicit a certain amount of pride, ultimately it is popular appreciation that history remembers.

Hegel also saw that fundamental to being human was the taking of risks in pursuit of this recognition. The ability to risk one’s life made someone the master of their own domain – an achievement of freedom that transcended both social constraints and the natural instinct to keep oneself alive. This is certainly the spirit that guided the actions of the RAF. Slaves to ideology, but masters of their own metaphysical place on Earth.

Yet a more rational pursuit of risk is to create art that has ambition and vision. To take an idea and explore its possibilities and potential. For it to be daring, clever and insightful. To push the boundaries of imagination, place it in the public realm – within the vulnerability of light – and hope that others will understand and appreciate its purpose.

Haines felt that he never found the reward for his risk. Following on from the Baader Meinhof album, the closing song on the fourth and final album by The Auteurs – before he went solo for diminishing returns – addressed this lack of recognition directly. With his requisite bitterness, but ever confident belief, Future Generation saw the then musical landscape being unreceptive to his genius, and insisted instead “the next generation will get it from the start.”4 Before concluding with the assertion that “This music could destroy a nation”. Which, to Haines, in his very British manner, is surely music’s point?

“What can you do when you’ve made your masterpiece? That’s what I did in the 90s. I was all over the 90s. I was all over in the 90s”

21st Century Man – Luke Haines

I was going to make the argument that both Brexit and the rise of Reform UK could be tied to the decline of the British music press. Without this combative relief value the country has turned to radical politics instead. But I thought it might be a bit of stretch. However, it’s an amusing thought nonetheless.

At the time of writing the Trump Administration has clearly manufactured a situation where it has sought to encourage violence, so it can respond with excessive force. This is very different to the conditions in West Germany in the 1970s, where the RAF, not the state, were the clear aggressors.

This would change with the fourth and final album by The Auteurs – How I Learned To Love The Bootboys. With a far broader range of instrumentation used in inventive ways. Quite frankly, it is an exquisitely crafted sophisticated pop record that Haines has every right to be disgruntled about its lack of public traction.

The irony here being that the 1990s were probably the last decade that someone like Haines could thrive. Without the British music press the cultural terrain nowadays would find his combative dark humour foreign, offensive and bewildering. This essay may meet the same response.