The Anti-Hegemonic Reflex

Former Australian prime minister Paul Keating's increasing hostility towards the United States – and sympathy for China – illustrates some deep psychological impulses within progressive politics

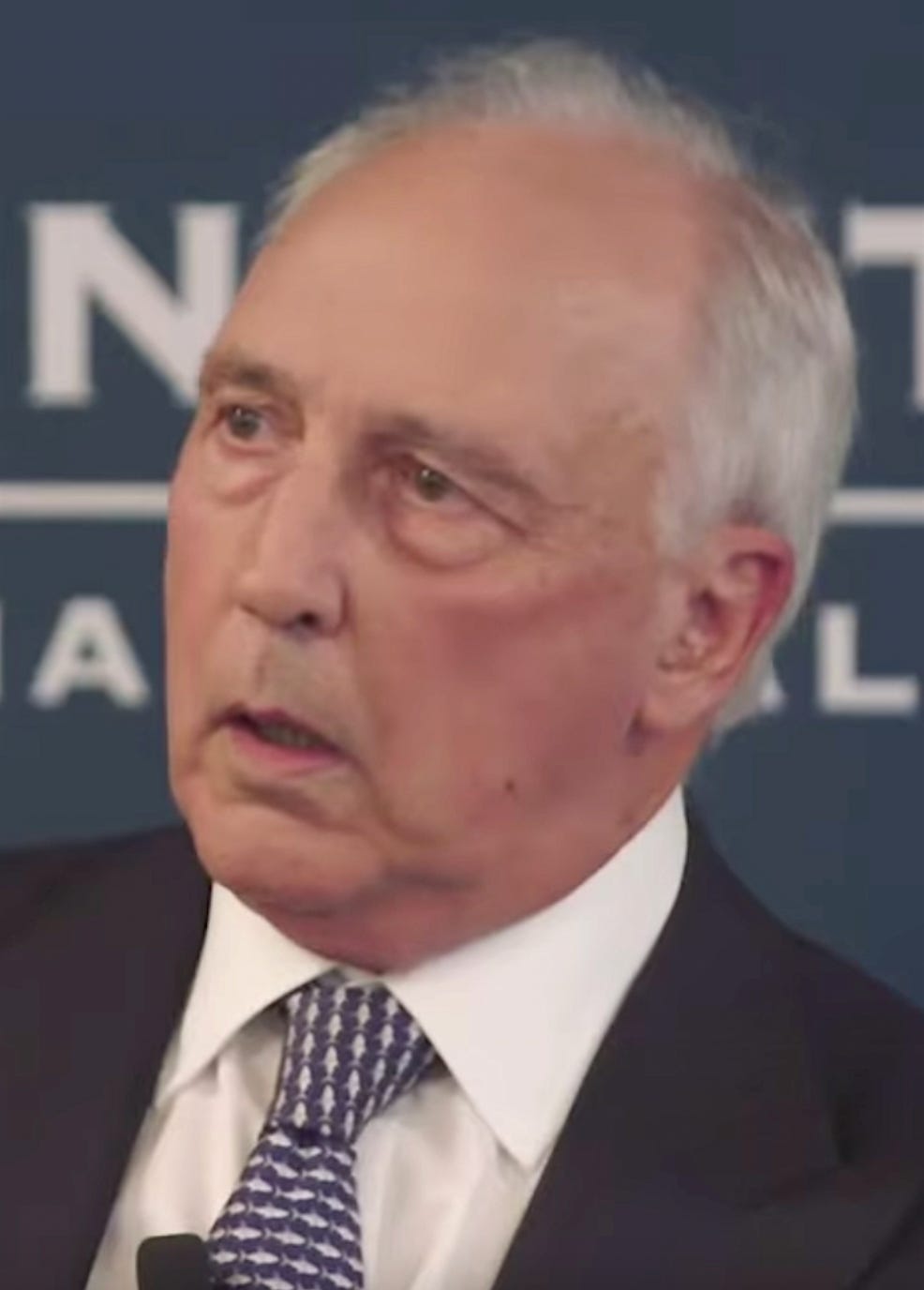

Over the past few months I have found myself incredibly frustrated with some major figures in Australia and their commentary on foreign policy issues. Former prime minister, Paul Keating, and former foreign minister and premier of New South Wales, Bob Carr, have both become increasingly vocal in their suspicion of Australia’s alliance with the United States. Holding a belief that Washington is “warmongering” in its attempts to deter a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, and that Australia has no right to be concerned about China’s increasingly aggressive behaviour in the South China Sea.

This week Keating again launched an extraordinary tirade against both Australia’s foreign minister, Penny Wong, and the head of Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, Mike Burgess.

Keating and Carr may not be consciously mimicking the talking points of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), but have certainly become a pair of very useful idiots. Men who have become increasingly bitter and resentful as they age, and have found a subject matter to gain themselves constant attention. And while attention-seeking may be part of the reason for their public pronouncements, their behaviour also demonstrates some key trains of thought and psychological impulses within progressive politics that are worthy of exploring. Both men were politicians from the Australian Labor Party.

The first component is a perspective towards deterrence. It is one of the great linguistic ruses to reframe deterrence as aggression. It relies on assumptions about who has the legitimacy to use violence in pursuit of their aims. When it comes to Taiwan, this assumption ignores – or doesn’t even consider – the desires of the Taiwanese people themselves to determine their own future. It believes that the desires of the CCP are vastly more important, and need to be met. Through violence if necessary. For men like Keating and Carr, to seek to deter this violence is therefore deemed a form of aggression.1

The U.S has certainly undermined its credibility to pursue a policy of deterrence with its arrogant, brutal and bumbling invasion of Iraq – an action that certainly lacked legitimacy – and a great amount of understandable cynicism has flowed from this. However, this doesn’t mean deterrence is itself wrong. In a world where belligerence exists – and may always exist – deterrence may, unfortunately, be the best tool we have to maintain peace.

There has always been a distrust of Australia’s alliance with the U.S within the country’s progressive politics. A distrust beyond the invasion of Iraq and the influence of the U.S’s current deeply troubling domestic politics. Progressive sentiment has an instinctive anti-hegemonic reflex that sees those who hold power as always being more suspicious than those who don’t. Therefore, as the world’s most powerful state, the U.S is automatically the world’s most suspicious actor.

There is an absolute necessity to scrutinise power, however, it is worth considering what the world might be like without U.S hegemony. Would an Asia dominated by Imperial Japan and a Europe dominated by either Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union be better? The alternative to U.S hegemony is not some utopia of peace and justice, it is most likely one of far worse hegemons – with not just an imperfect commitment to the liberalism that has allowed a great many countries like Australia to flourish, but an active hostility towards it.

Yet as our political discourse is conducted through a permanent binary reaction, and because an obsession with great power politics is what drives “nationalist”, or group, thinking in George Orwell’s framing, a reflexive anti-Americanism leads to an instinctive sympathy for the U.S’s current major competitor – the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Through this international negative partisanship, if Washington is irresponsible and suspicious, then Beijing must be responsible and trustworthy by default. And, by extension, Beijing’s attempts at exerting its power are therefore more legitimate.

This is a dangerous psychological trap to fall into.

It’s also one that I am rather unsympathetic towards. As for “progress” to mean anything it has to be tied to a set of principles that actually produce positive outcomes for humanity. Opposition to authoritarianism needs to be at its core. Although the striving for perfection that is inherent in a progressive disposition means that authoritarianism is often seen as an attractive means to an end.

Given that we often orientate ourselves by labels rather than ideas and outcomes, we frequently fail to see what is right in front of our noses. Several months ago after another one of Keating’s missives – and the cheering this produced on Twitter – in frustration I scribbled down some notes. Usually I don’t like to write in anger, or with snark, and if I do I tend to revisit these ideas and shift the tone. But I think the tone may actually now be necessary when addressing how odd this sympathy for the PRC is.

What exactly is “progressive” about the People’s Republic of China?

Is it the cultural genocide and ethnic oppression in Tibet and Xinjinag? The bellicose chest-beating nationalism? Threats to invade democratic and liberal Taiwan? The extraterritorial claims over all ethnic Chinese? The suppression of freedom of speech, assembly and information? Its ubiquitous surveillance state? The promotion of gender hierarchies, hostility towards homosexuality, and active concern about “sissy men”? Is it the illiberal state-led capitalism and vast income inequality - with the top 10% owning 70% of the country’s wealth? Its use of economic coercion as a tool of statecraft? The taking of foreign hostages? The aggressive flouting of international law in the South China Sea? And its massive military build up?

Or is it just because China is an adversary to the United States and it says “communist” on the tin and a) there’s a lack the curiosity to actually open the lid and look inside, and b) there’s a latent progressive tendency to believe that communism is “in theory” still the ideal to strive towards?

Part of this is ignorance about the kind of party the CCP is, but it is also about how a progressive disposition thinks about power relations. There is a tendency to mistake hegemony for a concentration of power. The U.S is undeniably powerful, but its hegemony has broadly presided over a period of decentralisation of power through liberal political and economic structures (however imperfectly). One only needs to return to the ideological challengers of the 20th Century – all centralising ideologies – to see how different the world could have been.

The true power of the people is one where individuals are trusted to make choices for themselves. Freedom of exchange flows from the same philosophical well as freedom of speech and assembly. There is, of course, no perfect decentralisation of power, and many companies and individuals have huge concentrations of wealth and influence. They tend to not have armies though. Their influence doesn’t extend to organised violence.

Authoritarian states see force as a central tool of statecraft. The PRC has used different forms of economic coercion - product bans, punitive tariffs, hostage taking, physical intimidation, and a system of rewards and punishments tied to other states’ degrees of deference. These actions are testing the waters of what it can get away with. A U.S that is less committed to defending liberal norms internationally means that these forms of economic coercion are likely to escalate and become far bolder.

We take it for granted that we can sail a cargo ship from Melbourne to Tokyo, or London to Singapore unobstructed. We fail to envisage a world where this might not be the case – where a power like the PRC decides what goods can and cannot be traded. We don’t contemplate what kind of effect that this would have – most of what we rely on for our day-to-day lives depends on current freedom of navigation.

An instinctive opposition to hegemony regardless of the structures it advances misdiagnoses our current international environment, and risks advancing the power of states that have a far more brutal view of hierarchy. These instincts are built on a refusal to think seriously about what ideas and structures actually advance human flourishing, and the clear-eyed recognition of alternative models that have little interest in this flourishing.

A core reason for this anti-hegemonic reflex is a progressive tendency to judge the actions of one’s own country (and its allies) more severely than those of other countries. This approach is driven from a good place – the need for self-scrutiny – but often devolves into a form of self-flagellation that struggles with objective analysis. Failing to identify real threats, and as well as consequences of what shifts in global norms would actually produce.

There is also the irony that this self-scrutiny is often only directed outwards at governments, rather than inwards at progressives’ own movements and dispositions. It refuses to seriously contemplate and interrogate the often brutal forms of anti-humanism that have been advanced in the name of “progress”. “That wasn’t real communism” isn’t a good enough response. Humans would rather live in political fantasy than go to ideological therapy.

This is an abandonment of critical faculties. A disinterest in thought. Although it can be difficult, careful consideration of current affairs involves not conflating how genuinely dangerous the Republican Party has become with a broader understanding of norms and structures that the U.S has advanced (while not overlooking its own breaking of them). At present, there is enough liberalism baked into the U.S, and enough decentralisation of power within it, to guard against Republican designs of becoming a party like the CCP (while acknowledging the serious damage they are doing in their attempts).

Yet, if liberalism’s primary defender in the U.S is deeply flawed, does that make liberalism deeply flawed? Liberalism’s genius lies in its ability to muddle through. Its ethos is one of striving for improvement within a pragmatic realisation that perfection cannot be achieved, and that there are genuine dangers in seeking to do so. For those who demand perfection, who forgo improvement in order to wait for utopia, liberalism can prove frustrating and breed cynicism, often coupled with conspiracism.

Although clearly not exclusive to it, there is unfortunate obsession with power within progressive politics. Not one that seeks to decentralise it, but an impulse that seeks to grasp it. For those who lust for great power, and those men like Keating who have held it and lost it, there is an emotional struggle with negotiating the world as humble a citizen. Sniping from the sidelines, and striving for headlines, are hollow attempts at public contribution. They are the arrows of resentment from men who cannot be satisfied with their past achievements.

Like most approaches to politics the anti-hegemonic reflex is driven from these personal psychologies. The things we think we are owed – rather than the duties and responsibilities we have – are projected onto both our domestic political systems and international relations. And while the anti-hegemonic reflex may claim to be suspicious of power, it doesn’t attach itself to advancing the interests of smaller states (see the callous disinterest in the welfare of Taiwan or Ukraine). It instead attaches itself to major ideological challengers in the hope of bringing down the hegemon. It’s not anti-power, but a lust for alternative power. Regardless of what this alternative represents.

This is very similar to how we view men’s “right to violence” within the household. Men, like great powers, are perceived to have domains that are legitimately theirs to control with force if necessary. Questioning this is deemed hostile to men’s superior interests. A very odd perspective for progressives to hold.