The Elephant in the Womb

The global decline in birth rates may be due to the greater expectations women now place on partnership and fatherhood, and men failing to meet the moment

Humanity’s current great structural problem is our decline in birth rates. This has moved from just being a phenomenon within highly developed, wealthy countries into becoming more widespread. Even countries that still have birth rates well above the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman, are seeing their figures decline. Given the exponential nature of the phenomenon, once the population starts to decline, it will decline rapidly.

Low birth rates impact every facet of human existence. The most direct dilemma they create is the greater burden on the working-age population to support those in retirement. But the issue extends to the ability to maintain local and national services, to what technological advances we are able to achieve (or preserve), what problems we are collectively able to solve, and all the way through to the global balance of power and the implications of which types of states can exert their will on the rest of the world.

The reasons to explain the decline in birth rates are numerous, from the waning of religious observance, the rise of women’s education, better access to contraception, general economic insecurity, the lack of affordable housing (with enough bedrooms for multiple kids), concerns about climate change, weaker social expectations around “settling down”, other delayed adult norms and less individual social resilience. Alice Evans has argued that the rise of smartphones and the enormous cultural shift they have created is also having a significant impact.

In the United Kingdom, Australia and United States, women state that they ideally would like more children than they are currently having. Which means that alongside the confluence of the reasons above, there may be another factor that is proving highly influential.

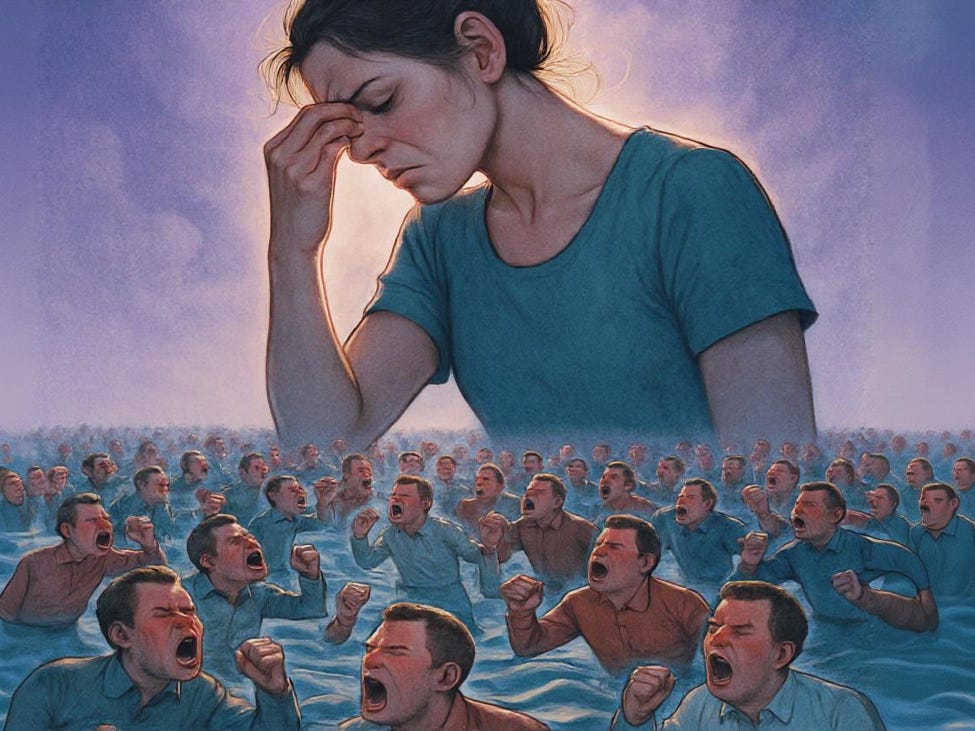

Yet this is a reason that people may find difficult to acknowledge or confront. Women nowadays – rightly – have a higher expectation of men for both partnership and fatherhood. Men, however, are not rising to the task. Instead, the response of many men to these new social conditions has been an intense wave of resentment and hostility – which is in turn spiralling up into our current political instability.

Like almost everything, the insanity of modern political culture is preventing us from seeing this issue clearly. Our current approach to politics can be formulated as – Person X says Y and I don’t like Person X therefore Y is wrong. And this formula has attached itself hard to this issue. Concern about low birth rates has been “coded” as a conservative issue, but this a deeply superficial understanding of their impacts.1

Certainly the pro-natalist movement has some unsavoury characters, from the attention-seeking weirdos Malcolm and Simone Collins2, to the 54 year-old teenage edgelord, Elon Musk. Many reactionary groups have seen declining birth rates as evidence that women should have never been allowed out of the house – hoping that the issue can drive a return to a world of women’s submission to men’s social control. Spend any time on Twitter and you’ll witness the most repulsive scumbags on the planet believing that the issue has given them free reign to relentlessly post vile and insane misogyny.

These reactions, and their political manifestations, are exacerbating the problem by making men even less appealing for partnership and fatherhood. As we can see from South Korea – a highly patriarchal society that hasn’t evolved as its women have become some of the world’s best educated (and most culturally savvy) – if men’s attitudes and broad social structures don’t change, women will simply avoid men altogether. And they will be entirely justified in doing so.

Yet the implications of this are dramatic. Societies without youth lack verve, imagination and confidence. Governments won’t see long-term investments as economically justifiable. Their focus will be on how to best manage decline – becoming highly anxious and combative in the attempt. The democratic calculations of political parties are completely different when a country’s median age is almost 50 – as Japan’s is – compared to a country with a median-age in the mid-20s. Democracy will become a game of protecting older generations’ advantages, rather than providing younger generations with opportunities. We already see this in housing policy throughout the West.

This means that the state of our menfolk is our most pressing political concern. Rather than being a “women’s issue”, declining birth rates should be seen as a men’s issue. It’s one of men’s behaviour, attitudes, and character. It’s one of how we, collectively, as men, develop a sense of responsibility. How we find positive purpose, duty, kindness, and personal humility. How we come to actually like women.

Men may find this offensive and difficult to accept. I can hear the “not all men” chants already. Yet instead of jerking our knees and clenching our fists, this requires us to stop, take a breath, and exhibit some maturity. At present there is a deep insecurity within masculinity and it is attaching itself to an intersecting web of negative influences and aggressive online movements. This includes people like Andrew Tate and Matt Walsh – tiny, pathetic, men who think that acting out the most brutal and clownish masculine stereotypes is what constitutes being a man.

Theirs is the chest-beating of humanity’s decline. A cultural impotence convinced of its own virility. Featherless peacocking. An approach to human relations so hilariously out of touch with current human conditions, yet spreading all the same. Creating a chasm between the sexes that is sending the species into a potentially precarious retreat.

Humans have a tendency to see our existence as a zero sum game. We believe that the more people there are, the less resources there are to be shared around. We retreat into groups and feel that other groups are unfairly receiving more of an imaginary finite pie. Yet the past few centuries have proved the opposite to be true. The extraordinary increase in comfort and luxury, as well as a vast reduction in global poverty, has been driven by our ability to collectively compound our resources for each other.3 The current wealth and creativity of humanity is inextricably tied to the revolutionary rise in people.

Now a similar revolution is taking place with the education and advancement of women. This is unlocking a vast new capability for humanity that had previously been suppressed. The problem is that this advancement doesn’t exist in a vacuum. These gains for women don’t come at the expense of men, yet many men think or feel they do. Zero sum thinking is difficult for us to overcome. Particularly when men’s sense of personal pride has been tied to a structural social superiority. New forms of social relations can feel like a loss.

The success of this revolution for humanity – and for humanity’s reproduction – therefore requires us to think about how we minimise men’s resentment towards women’s agency and advancement. Or, ideally, for it to gain enthusiastic male support.

What we need is a masculinity that is pleased that women are flourishing. Men who understand this as a strengthening of humanity, and recognise that it contributes to the conditions of their own advancement. I suspect this would be highly attractive to women.

To build such men we are required to think seriously about masculinity and what it needs from our social structures, without returning to structures that disadvantage or oppress women. As we are now seeing, when women are given freedom and opportunity they thrive, but young men especially require greater guidance, purpose and discipline. There’s an emotional fragility to masculinity that means men struggle without social reinforcement. Without this reinforcement, men become agitated, and when men get agitated they tend to get agitated straight through Poland.

As Richard Reeves has written in his book Of Boys and Men, manhood is something that men feel the need to continuously achieve. It is something that needs to be “won” and won again. “But what can be won can also be lost. Hence the fragility.”4 This means that we now require more sophisticated methods of providing social reinforcement.

Reeves argues that due to boys maturing more slowly than girls they should start school a year later – what is called “redshirting”. Across every measure of educational success from kindergarten up to post-graduate studies, girls and women are now overwhelmingly out performing boys and men. This is leaving young women without a large cohort of young men who could be considered suitable mates.5 Starting school a year later gives boys more time to mature into both the educational and social aspects of schooling.

Writing recently in the New York Times, Reeves and Robert D. Putnam highlight that the early 20th Century also experienced a crisis of masculinity. The response to this in the United States was a wide-ranging establishment of new civil society groups designed to channel boys and men’s chaotic energy into positive outlets. Big Brothers and the Boy Scouts were founded, and there was huge expansion of youth sporting leagues and athletic associations. The objective was to create a “mature, pro-social manhood”. What was critical to this was the leadership of other men.

Yet given the relentless cynicism of our current era – and the online distractions that compound men’s social alienation – a firmer hand may be required. Last year, while attending the Helsinki Security Forum, I had the opportunity to visit the Santahamina military base and speak with some young men doing their national service. Finland’s mandatory national service for all adult males is not solely about the threat from Russia, it is about the socialisation of young men into society. It provides them with professional development, social capabilities and most importantly a sense of purpose and civic responsibility.

Previously I had been suspicious of the macho culture within militaries, and how national service may encourage and imprint these traits onto young men wholesale. Yet, defence forces may be unique as institutions that are capable of providing discipline and strict social expectations on young men without making them feel like their masculinity is being threatened. National service may enable young men to “win” their manhood early, and hopefully develop the character and emotional security to not have to constantly prove this manhood in ridiculous and dangerous ways as they rejoin society.

What I observed when talking to these young Finnish men was a serious sense of duty. They understood the reasons why they were there and the importance of what they were doing. Of course, sharing a 1340 kilometre border with a permanently belligerent country provides stark clarity about the world for the Finns, but duty is something we can foster within young men without having Finland’s tragedy of geography. If men need a grand purpose, then they are now being presented with one.

Rather than see women’s greater expectations on partnership and fatherhood as an imposition and react with resentment and malice, there’s an opportunity to see this as an opportunity and responsibility. For men to carry these expectations on their shoulders. Men’s need for pride and status may be persistent, but it is also malleable and harnessable. There are enormous prideful rewards to be won in impressing women with your character. In presenting yourself as fatherhood material.

For the bulk of human history it didn’t matter to the species that men didn’t particularly like women. But now it does. The biological conditions for reproduction are insufficient, it is the social conditions that have become paramount. It remains an extraordinary risk for women to go anywhere near a man, and it is a risk many women are now unwilling to take.6 We, as men, have to acknowledge this and take responsibility for rectifying it.

Due to biological realities, the vast weight of humanity’s existence has been carried by women. The effort men have needed to make by comparison has been miniscule. But the world is now facing an era where men’s tiny biological efforts need to be supplemented with a great new endeavour in temperament and virtue. The times have changed, and now humanity’s biggest question is whether men can meet them.

The “coding” of everything now is also a massive problem with modern politics. It’s a refusal to think. We’re losing the ability to be able to contemplate ideas on their own merits.

The strategy the Collinses mention in the piece to “troll the left” is precisely the opposite of what is required to advance the cause they claim to be advancing. And it’s an example of the cancer that is at the heart of modern politics. A complete abandonment of persuasion. A belief that there is nothing but the heckling of politics as a team sport.

This compounding of resources for each other is why even though Japan is shrinking, Tokyo is growing. As population declines the need to be in urban centres increases.

Richard V. Reeves, “Of Men and Boys”, Page 80.

Stephanie H Murray has argued that middle and upper class highly educated women are still marrying at consistent rates. This makes sense given that they have the capabilities to pick out the men who can meet their expectations. But due to there being less university-educated men they are also plucking out of the highest earning non-university educated men. What she identifies is a working class phenomenon that women are unable to find suitable partners. Even if these women aren’t gaining degree or post-graduate degrees, there is still a social transfer of knowledge that is uplifting women’s expectations.

The hilarious social media response to the “man vs bear in the woods” hypothetical was for men to think they could threaten women into not choosing the bear.

Excellent article, very intuitive.

I think about the population situation a lot, but hadn't considered this viewpoint. It's also related to the ACX not-a-book review titled Dating Men in the Bay Area which discusses the fact that for millenia there was a clear map to manhood, but currently the only maps there are don't make sense. Also, nice title :)