Week 39: Tongues in Chic

The Finns take their official bilingualism very seriously, and often amusingly so.

Over the weekend I was in Helsinki for the Helsinki Security Forum. There were a few ideas I gathered at the forum that I hope to write about in the coming days, but aside from the forum itself the opportunity to be back in Helsinki is one I relished.

Although the competition is fierce, Helsinki may be my favourite Nordic city. Although lacking the hustle and the bustle that I usually prefer in a city, Helsinki is both very pleasant and cool. And Finland has some quirks and a distinctive culture that marks it as quite distinct from the other countries in the region.

Although Finland is a member of the Nordic Council, the Finnish language is not a Nordic language – that is, it’s not descendant from Old Norse (as Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Icelandic and Faroese are). Finnish, instead is a Uralic language - originating from the east of the Ural mountains. Although Finnish – and Estonian and the Sámi languages of the Artic – have been in northern Europe for far longer than their distant cousin Hungarian has been in central Europe (which I wrote about earlier on my visit to Budapest).

However, Finland has a long Nordic history as part of the Swedish Empire from the mid-1200s through to 1809. – which is where it derives its Nordic identity from. At its height, the Swedish Empire dominated the Baltic Sea region. I wrote about some of this history for The Lowy Institute a couple of years ago while catching a ferry across the Baltic from Stockholm to Helsinki. I also happen to be typing this on a ferry going in the other direction following the Security Forum.

Which such a long history as part of the Swedish Empire, the Swedish language has dominated Finland. It was only in 1863 – over 50 years after Sweden lost control of the territory – that Finnish became an official language of Finland alongside Swedish. This despite it being overwhelmingly the majority language. There is an excellent episode of the BBC Radio 4 programme In Our Time on The Kalevala, a national epic poem based on Finnish folklore whose influence – and inspiring of Finnish pride – led to Finnish gaining official status in the country.

Yet due to its history, there remained a significant Swedish-speaking elite in the country who dominated politics, commerce, science and the arts. Swedish was the prestige language. The way power and influence is distributed in societies means that when there is such a prestige language gaining an equal footing – or even exerting majority power – often takes generations without a violent revolution (and violent revolutions usually just install a new elite).

Eventually Finnish would exert its numerical dominance – and become the language of politics, commerce, science and art itself. In this, it was helped by a significant migration of Swedish-speakers in the 20th Century to Sweden. In 1900, Swedish speakers comprised around 13% of Finland’s population, this has now been reduced to a current population of just over 5%.

However, during this time Swedish has remained a co-official language of Finland with Finnish. This has been due to the canny pragmatism of the Swedish People’s Party, a party who have been part of almost every coalition government since the 1940s, and have made sure that the Swedish language has maintained official status in the country. Although they are far from a single issue party – they have an extensive party platform, and take their coalition cabinet roles very seriously. The party’s former leader, Anna-Maja Hendricksson (who resigned the post in July), is the country’s longest serving Minister of Justice – holding the post for 12 years.

Coincidently on Friday morning I was paying a visit to Oodi, an incredible new library in Helsinki, and Hendricksson was inside having some photos taken. Presumably for her new role as a member of the European Parliament. I thought about approaching her for a chat, but she quickly scurried for the door after finishing with the photographer.

Despite being reduced to a small percentage of the population, Swedish speakers remain heavily concentrated in coastal areas. Under Finland’s Language Act, local councils are divided into being unilingual or bilingual. A council must provide bilingual services if the area has at least 8% – or at least 3000 people – of one of the two languages’ speakers. The map below shows the council areas where Swedish is either the unilingual language, the majority language, or the minority language.

The autonomous province of Åland is Swedish-speaking, and is not subject to the language laws of the rest of Finland. But at just 26,000 people it is only 0.3% of the total Swedish-speaking population of Finland.

Finland is quite distinct in the lengths it goes to maintain bilingualism in the areas that warrant it, particularly in comparison to other bilingual states. In New Brunswick in Canada they’ve found a neat way to format street signs as – Rue [Name] Street – to make it bilingual. In Finland, however, official bilingualism is taken to a more extreme level, with each street, and each suburb having two different names – a Finnish and a Swedish one.1

In Helsinki all street names and suburbs were originally in Swedish, given that Swedish was the language of administration when the city of founded and grew. It wasn’t until the mid-1940s that streets and suburbs were given Finnish names. However, rather than replacing the Swedish names, they instead gave each street and suburb an additional Finnish name.

Language laws state that the language that is in the majority in a specific council area has its names for the town or suburb, street and traffic signs first. This leads to incredibly amusing scenarios where councils with around a 50/50 split of Finnish and Swedish speakers constantly have to change their signage as people move in and out of the area – as explained on a short BBC World Service video from a few years ago.

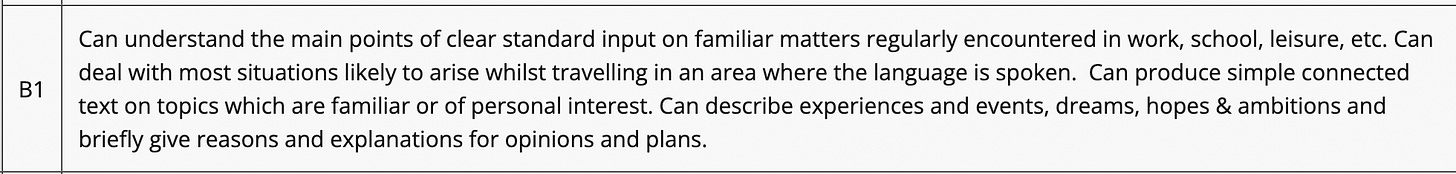

While government services at both a central level and local level where warranted are provided for the Swedish-speaking minority, given that Finnish is the overwhelmingly dominant public language Swedish-speaking Finns are generally also fluent in Finnish. However, Finnish-speaking Finnish also have to learn Swedish at school. In order to enter into university, one must demonstrate at least a B1 level of knowledge of both national languages.

This means most educated Finns are at least trilingual, given that English is also a compulsory subject throughout school, and like other Nordic countries it is spoken with native-level fluency.

In bilingual council areas